Breadcrumb

- Home

- Nobel Peace Prize 2014 Laureate Kailash Satyarthi

Nobel Peace Prize 2014 Laureate Kailash Satyarthi

Main navigation

I have nominated Kailash Satyarthi for the Nobel Peace Prize almost every year since 2006. This excerpt from my nomination letter describes why he so well deserves the prize awarded this year.

From my perspective as a professor of law and legal history, I continue to believe that no one, who is living today, comes to mind who is more deserving of this prize for the extraordinarily important work of changing the lives of children sent to labor in conditions approximating slavery. By recognizing Mr. Satyarthi's mission and his achievements the Nobel Committee would shine the light of recognition on international efforts to end the misery and exploitation of child labor.

I commend Mr. Satyarthi to you for several reasons: the strength of his character, his personal commitment and sacrifice, his insight and practical intelligence, and his effectiveness in achieving real social change on several successful levels of engagement to end the practice of child labor. Mr. Satyarthi was among the first to recognize the widespread significance of freeing children from bondage. He views laboring children as the least well-off class of persons in the world. He saw the need to free children from bondage for the sake of the adults they will become, for the democratic future of the nations they will inhabit, for the benefit of the economies of their developing countries, and for the peace of the world.

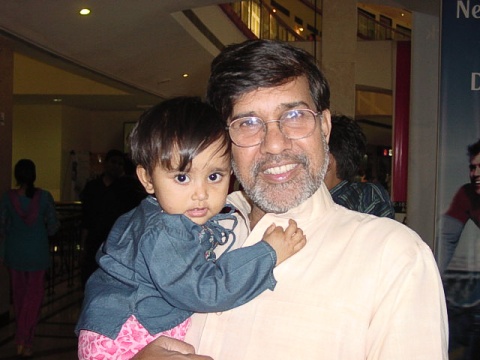

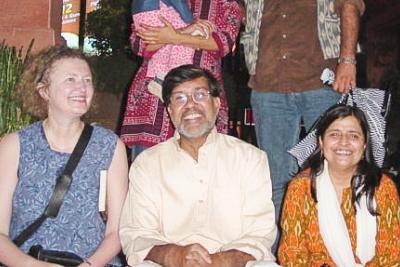

I was privileged to observe Mr. Satyarthi and his work by living in his extended family for a month last year. I traveled to Delhi to learn from him and about his work. I came to know Mr. Satyarthi because of my scholarly interest in the legal history of slavery and freedom in the United States. Quite by chance. I attended a speech he gave to American teachers about educating American children to the circumstances of children who are set to labor for the benefit of others. Because I read widely and live in academic and intellectual circles in the United States as well as Europe, (Yale Law School, the Juridicum in Vienna, as well as my home university in Iowa), I had heard many of the world's most famous thinkers, speakers, politicians, and activists. Yet I simply had never seen a person speak as elegantly, pragmatically, and completely extemporaneously about a problem requiring the world's conscious attention. He spoke of the need to free the world's current and future generations of children from the life-limiting experience of child labor. Intrigued by the depth of his understanding, I questioned him further. He answered as someone who knew first-hand the difficulties of liberating enslaved and long dependent peoples and as someone who had reflected deeply upon issues that I had spent decades studying. Mr. Satyarthi was optimistic, thought he had seen some of the most desperate case of human enslavement in quarries, brick kilns, and locked factory sheds. Mr. Satyarthi had practical answers to what others saw as a hopeless situation, and more than that, he had achieved clearly set and practical objectives to bringing about a world free from child labor.

It is easy to understand the despair of enslaved people, where there is no force above to appeal to and no help for those below. Mr. Satyarthi spoke instead of creating schools for learning the skills of independence and having the freedom to go to school to learn. The more he responded to my questions, the more I became convinced that this individual has thought out the ramifications of the emancipatory process that he was bringing about in India and other parts of the world. I devoted my sabbatical leave to traveling around the world to see for myself how this man had accomplished so much, against all odds. I can attest to having the privilege of observing and learning from one of the world’s most extraordinary men, and the only person I can imagine nominating for the Nobel peace prize.

In terms of his character, Kailash Satyarthi is schooled in the philosophic tradition of the Vedas and Gandhi, in peace and the nobility of all human beings. He laughs easily, smiles often, and listens carefully to everyone. He is a practical man with an engineer’s thorough understanding of the physical, economic and material realities of planning and logistics. He is a charismatic storyteller who is able to address villagers’ children as easily as erudite audiences of world leaders. He has a knack for knowing when and how to use universal or specific cultural images as well as the local vernacular to persuade. And, most poignantly, he inspires the faith and trust of perfect strangers, enslaved, abused, and downtrodden people who follow him quickly, as they must on first meeting, if he is to lead them out of the captivity of quarries and warehouse sheds during a peaceful rescue.

Kailash learns from his mistakes. His motto is never to conclude with a period full stop, always with a comma, to keep going toward the goal. Although both child labor and debt bondage are illegal in India, child labor is such a common practice that many would consider ending child labor to be an impossible goal.

From a personal experience evolved the opportunity for him to learn the technique of intervention to peacefully rescue bonded laborers and children from those who held them to labor. Both debt slavery and child slavery have occupied Kailash’s efforts. The interventions that he engages in with the help of hundreds of local volunteers are carefully planned out, legally sanctioned by writs of habeas corpus, and accomplished non-violently. He can appropriately be credited with participating in and assisting in the planning of the liberation of thousands of adults and children held in modern slavery. He reunites trafficked children with their long lost families and trains them with skills to prevent their further exploitation.

Kailash realized that simply removing laborers from their enslavers was not enough to set them upon the path of self-sufficiency and independence. Enslaved adults and child laborers had been psychologically imprinted with the circumstances of their enslavement, such that simply releasing them from one enslaver could leave them susceptible to exploitation by the next opportunistic person to come along. Hence, Kailash envisioned and brought about the idea of rehabilitation by founding ashrams that his organization runs in Northern India. After children have been re-united with their families, and with the family’s consent, the children spend six months at the ashram. The objective of the time spent at the ashram is to rebuild the child’s self-esteem, skills training, and awareness of the importance of breaking the cycle of child slavery so that the child can return to his village empowered to protect himself and others. I visited all three of the children’s ashrams run by the Global March, and the children were truly a joy to see. The day begins with exercise and a particularly Indian therapeutic technique of practiced laughing. Reading, writing, language skills, mathematics, music therapy, and life skills follow in the holistic approach to rehabilitating children who have lost some part their childhood and personal development by being held as slaves.

The interventions may seem to be the most dramatic of Kailash’s many achievements but Kailash has achieved more widespread gains by other means. In 1989, he realized that for every 50 children that he was able to rescue from confined labor, hundreds more were being trafficked to replace them. Understanding that some different tactic was necessary, Kailash set about at great personal cost to organize consumers of products produced by enslaved children. He first imagined and then brought about the concept of Rugmark, a method of branding carpets that have been produced without the use of child slavery. Organizing the consuming public requires a highly difficult logistical campaign. It had never been accomplished on quite the scale that Kailash imagined. Nonetheless, Kailash persuaded church leaders and humanitarian groups in Germany and the U.S., the two largest buyers of Indian carpets, to be aware of whether the products were made by children. Kailash institutionalized a method for alerting the market consumer to the authenticity of the child labor free brand. Rugmark works because it uses a combination of consumer awareness, willing producer compliance, and authentication of the marking process. By focusing on the key market factors, Kailash moved away from rescue to pro-active engagement in the market process. In this respect, the Rugmark initiative has become the gold standard for consumer awareness. The large retail importer IKEA has now adopted a similar method.

In a culture where it has long been accepted that children, especially of the lowest castes and classes, are set to work at an early age, Kailash and his organizations, BBA and SACCS, proceeded to organize consciousness-raising marches across the country. In four or five successive marches, each more ambitious than the one before, BBA and SACCS have walked the length and breadth of India and South Asia. In 1998, Kailash organized a Global March, starting on three different continents, to raise consciousness of the issue of the worst forms of child labor. The Global March culminated in an unprecedented opportunity for poor children to meet in Geneva at ILO headquarters and urge that body to adopt the ILO convention on the worst forms of child labor. The logistical dimensions of this world-consciousness-raising event are almost overwhelming, and pulling off the world-wide Global March, with consciousness-raising events in so many different countries and cultures would have been an accomplishment in itself. To have culminated in Geneva to urge the ILO to adopt the convention as soon as could possibly be accomplished, and to have the ILO do so is beyond remarkable. It is extraordinary, almost the stuff of legend.

The consciousness-raising took an additional grass-roots dimension when Kailash realized that it was important to educate those villages that had been the source of trafficked children to keep their children at home and send them to school. Currently, SACCS has effected a child-friendly village program which is similar in some sense to the trademarking of the Rugmark experience. Villages can be accorded special recognition when they have organized a school for their children to attend and have refused to allow any of their children to be sent into labor for one year. The child-friendly village designation is its own brilliant contribution to the overall scheme. This program interrupts the cycle of re-enslavement and changes the local expectation that children can be sent off to work. Kailash believes, and many theorists would agree, that there will be more employment for adults under more favorable terms if children are protected from laboring in the marketplace and sent to school. Some theorists estimate a one-to-one replacement rate, that one job forced upon a child is one less job for an adult. Thus, child-friendly villages should aid in the countryside’s development program, not only by providing education to the children but by reserving jobs for adults who have at least some opportunity to improve their working conditions, as compliant children do not.

The child-friendly village concept has another extraordinarily favorable additional benefit. Many of the villages that had previously sent children with traffickers were run by village elders, who by tradition were selected only from the men of the village. The child-friendly village program encourages, and requires for certification, that children’s councils and women’s councils be organized to routinely meet with the established all-male village elders and voice their concerns. The village elders are required to meet regularly with the children’s and women’s councils in order for the village to receive the child-friendly village designation. Thus, the child-friendly village concept has had the grass-roots effect of restructuring the deliberation processes of the village to include two groups traditionally excluded, women and children.

Kailash Satyarthi has placed the issue of compelled child labor on the world’s agenda and designed and executed means of turning the tide. What Kailash Satyarthi has envisioned in the circumstances of India in each of these initiatives -- peaceful intervention, rehabilitation, consumer organization and producer compliance with monitoring, and child-friendly villages -- are models to be learned from in other parts of the world. To that end, Kailash Satyarthi is the first to say that each application must grow out of the culture in which it is set, and must be carried out by the people closest to the problem. Nonetheless, Mr. Satyarthi’s work and methods of eliminating child labor in India’s quarries, brick kilns and the carpet industries are being adapted to chocolate manufacturers, cosmetic companies, soccer balls, and fireworks on other continents. Mr. Sathyarti continues to advance this cause by his encouragement, inspiration, insight, collaboration and persevering efforts. The ripple effect is indeed a world-wide effort to bring about the preconditions of world peace.

Press Links:

2014 Nobel Peace Prize Laureate Satyarthi nominated by Senator Harkin and Professor VanderVelde